Why Philosophy?

Returning to the Historian Will Durant

I’m often asked why one reads philosophy, what practical value will it have?

Why must everything have practical value is a good question itself.

I’ve read many views on why philosophy, the best of which I think came from the British philosopher Isaiah Berlin. He told journalist Bryan Magee in his wonderful philosophy series back in the 70s and 80s for the BBC that the purpose of philosophy was to find the questions we haven’t found yet. “The great hallmark of philosophy is that you don’t know how to proceed.” He goes on to say that once philosophy has come up with the questions, it passes them on to science and heads back to the unknown.

Recently, I discovered a wonderful book from 1926, The Story of Philosophy, by the historian Will Durant, which begins with an introduction devoted to why we do philosophy. Back in college, I had a teacher who often quoted from Will Durant, so reading the book reconnected me with my first foray into understanding Western Civilization. Perhaps we were studying the Norman invasion of England or the democracy of ancient Athens; this teacher would be lecturing in front of the chalkboard, writing down dates, and giving us a timeline that we knew would be on the test. Then he would say, here’s what Will Durant says about it, reading us one marvelous quote after the other, which filled our imagining of history with shapes, colors, and people.

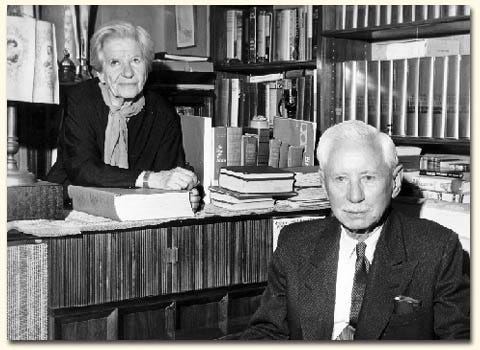

Durant was a historian from the early and mid twentieth century most known for his 11-volume work, The Story of Civilization. He wrote it with his wife Ariel and published it ongoing between 1935 and 1975. He and his wife were jointly awarded the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction. Later, he was given a Presidential Medal of Freedom. What I haven’t known all these years was that Durant was a philosopher as well. It was his book The Story of Philosophy which became an unlikely bestseller back in the 1920s and gave him and Ariel the money to travel the world and pursue their history writing.

Durant begins the work on philosophy with an argument for the purpose of philosophy written for the layperson, for the general audience. He argues for the “dear delight” in seeking truth and the meaning which Browning said "is my meat and drink”.

“There is a Pleasure in philosophy, and a lure even in the mirages of metaphysics, which every student feels until the coarse necessities of physical existence drag him from the heights of thought into the mart of economic strife and gain. Most of us have known some golden days in the June of life when philosophy was in fact what Plato calls it, “that dear delight”; when the love of a modestly elusive Truth seemed more glorious, incomparably, than the lust for the ways of the flesh and the dross of the world. And there is always some wistful remnant in us of that early wooing of wisdom. “Life has meaning,” we feel with Browning—“ to find its meaning is my meat and drink.”

So much of our lives is meaningless, a self-cancelling vacillation and futility; we strive with the chaos about us and within; but we would believe all the while that there is something vital and significant in us, could we but decipher our own souls. We want to understand; “life means for us constantly to transform into light and flame all that we are or meet with”; we are like Mitya in The Brothers Karamazov—“ one of those who don’t want millions, but an answer to their questions”; we want to“seize the value and perspective of passing things, and so to pull ourselves up out of the maelstrom of daily circumstance.

We want to know that the little things are little, and the big things big, before it is too late; we want to see things now as they will seem forever—“ in the light of eternity.” We want to learn to laugh in the face of the inevitable, to smile even at the looming of death. We want to be whole, to coördinate our energies by criticizing and harmonizing our desires; for coördinated energy is the last word in ethics and politics, and perhaps in logic and metaphysics too.

“To be a philosopher,” said Thoreau, “is not merely to have subtle thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so to love wisdom as to live, according to its dictates, a life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity, and trust.” We may be sure that if we can but find wisdom, all things else will be added unto us. “Seek ye first the good things of the mind,” Bacon admonishes us, “and the rest will either be supplied or its loss will not be felt.” Truth will not make us rich, but it will make us free.

Some ungentle reader will check us here by informing us that philosophy is as useless as chess, as obscure as ignorance, and as stagnant as content. “There is nothing so absurd,” said Cicero, “but that it may be found in the books of the philosophers.” Doubtless some philosophers have had all sorts of wisdom except common sense; and many a philosophic flight has been due to the elevating power of thin air.

One of his major themes is to compare philosophy with science, where he echoes the thoughts of Isaiah Berlin:

Let us resolve, on this voyage of ours, to put in only at the ports of light, to keep out of the muddy streams of metaphysics and the “many-sounding seas” of theological dispute. But is philosophy stagnant? Science seems always to advance, while philosophy seems always to lose ground. Yet this is only because philosophy accepts the hard and hazardous task of dealing with problems not yet open to the methods of science—problems like good and evil, beauty and ugliness, order and freedom, life and death; so soon as a field of inquiry yields knowledge susceptible of exact formulation it is called science. Every science begins as philosophy and ends as art; it arises in hypothesis and flows into achievement.

Philosophy is a hypothetical interpretation of the unknown (as in metaphysics), or of the inexactly known (as in ethics or political philosophy); it is the front trench in the siege of truth. Science is the captured territory; and behind it are those secure regions in which knowledge and art build our imperfect and marvelous world. Philosophy seems to stand still, perplexed; but only because she leaves the fruits of victory to her daughters the sciences, and herself passes on, divinely discontent, to the uncertain and unexplored. Shall we be more technical? Science is analytical description, philosophy is synthetic interpretation. Science wishes to resolve the whole into parts, the organism into organs, the obscure into the known. It does not inquire into the values and ideal possibilities of things, nor into their total and final significance; it is content to show their present actuality and operation, it narrows its gaze resolutely to the nature and process of things as they are.

The scientist is as impartial as Nature in Turgenev’s poem: he is as interested in the leg of a flea as in the creative throes of a genius, But the philosopher is not content to describe the fact; he wishes to ascertain its relation to experience in general, and thereby to get at its meaning and its worth; he combines things in interpretive synthesis; he tries to put together, better than before, that great universe-watch which the inquisitive scientist has analytically taken apart.

Science tells us how to heal and how to kill; it reduces the death rate in retail and then kills us wholesale in war; but only wisdom—desire coordinated in the light of all experience—can tell us when to heal and when to kill. To observe processes and to construct means is science; to criticize and coordinate ends is philosophy: and because in these days our means and instruments have multiplied beyond our interpretation and synthesis of ideals and ends, our life is full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. For a fact is nothing except in relation to desire; it is not complete except in relation to a purpose and a whole.

He goes on to stress that, unlike science, philosophy can give us wisdom:

Science without philosophy, facts without perspective and valuation, cannot save us from havoc and despair. Science gives us knowledge, but only philosophy can give us wisdom. Specifically, philosophy means and includes five fields of study and discourse: logic, esthetics, ethics, politics, and metaphysics. Logic is the study of ideal method in thought and research: observation and introspection, deduction and induction, hypothesis and experiment, analysis and synthesis—such are the forms of human activity which logic tries to understand and guide; it is a dull study for most of us, and yet the great events in the history of thought are the improvements men have made in their methods of thinking and research.

He then gives various branches of philosophy and argues for a total understanding of philosophy through the history of the great philosophers:

Esthetics is the study of ideal form, or beauty; it is the philosophy of art. Ethics is the study of ideal conduct; the highest knowledge, said Socrates, is the knowledge of good and evil, the knowledge of the wisdom of life. Politics is the study of ideal social organization (it is not, as one might suppose, the art and science of capturing and keeping office); monarchy, aristocracy, democracy, socialism, anarchism, feminism—these are the dramatis personae of political philosophy. And lastly, metaphysics (which gets into so much trouble because it is not, like the other forms of philosophy, an attempt to coordinate the real in the light of the ideal) is the study of the “ultimate reality” of all things: of the real and final nature of “matter” (ontology), of “mind” (philosophical psychology), and of the interrelation of “mind” and “matter” in the processes of perception and knowledge (epistemology). These are the parts of philosophy; but so dismembered it loses its beauty and its joy.

We shall seek it not in its shrivelled abstractness and formality, but clothed in the living form of genius; we shall study not merely philosophies, but philosophers; we shall spend our time with the saints and martyrs of thought, letting their radiant spirit play about us until perhaps we too, in some measure, shall partake of what Leonardo called “the noblest pleasure, the joy of understanding.” Each of these philosophers has some lesson for us, if we approach him properly.

“Do you know,” asks Emerson, “the secret of the true scholar? In every man there is something wherein I may learn of him; and In that I am his pupil.” Well, surely we may take this attitude to the master minds of history without hurt to our pride! And we may flatter ourselves with that other thought of Emerson’s, that when genius speaks to us we feel a ghostly reminiscence of having ourselves, in our distant youth, had vaguely this self-same thought which genius now speaks, but which we had not art or courage to clothe with form and utterance. And indeed, great men speak to us only so far as we have ears and souls to hear them; only so far as we have in us the roots, at least, of that which flowers out in them.

We too have had the experiences they had, but we did not suck those experiences dry of their secret and subtle meanings: we were not sensitive to the overtones of the reality that hummed about us. Genius hears the overtones, and the music of the spheres; genius knows what Pythagoras meant when he said that philosophy is the highest music. So let us listen to these men, ready to forgive them their passing errors, and eager to learn the lessons which they are so eager to teach. “Do you then be reasonable,” said old Socrates to Crito, “and do not mind whether the teachers of philosophy are good or bad, but think only of Philosophy herself. Try to examine her well and truly; and if she be evil, seek to turn away all men from her; but if she be what I believe she is, then follow her and serve her, and be of good cheer.”

Durant was quite prescient for our times in that he devoted his life to preserving the Western tradition. This is not to say that he was not interested in Asia or the East. He chided the narrow-mindedness of what is now known as Eurocentrism by pointing out in his book Our Oriental Heritage that Europe was only "a jagged promontory of Asia." He complained about "the provincialism of our traditional histories which began with Greece and summed up Asia in a line" and said they showed "a possibly fatal error of perspective and intelligence.”

Durant thought of philosophy as total perspective or seeing things from the whole. His life long project was to humanize history, which in the early twentieth century was already being carved up into ever and ever more sub disciplines. Writing the history of all civilization is a tremendous feat. And he brings this totality to his views on philosophy early in his writing career. Philosophy too has become an esoteric specialist field. Is this why we don’t see more philosophical arguments in the news? Journalists obviously think it is beyond the grasp or somehow inappropriate for their subscribers. Philosophy simply asks the big questions, the next questions. If philosophy is out of reach then it’s poorly written. Durant reminds us that “the story of” philosophy must always be connected with the humans who pursue it.