The Gene

And The Podcast Interview which Led to My Midlife Crisis

The Interview

It was a summer morning with dense fog up from the Santa Cruz coast. At around 11:15 it began to clear, and sunlight was cutting through like a Japanese blade from the redwood branches outside in through the living room window behind my chair. I was at work--- experiencing one of the most significant moments of my intellectual development as well as that of my career. I was on a Skype call with the English philosopher of biology, John Dupre. A Handel oratorio could not have brought more excitement.

“What is a gene?” John Dupre asked. “Does it really exist?”

Of course it does! I thought to myself loudly but silently, listening on to the silver-haired philosopher go into complications about the concept of the gene. Does it exist!

This is absurd, I thought. What about the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes which produce proteins that help repair damaged DNA? Mutations in these genes lead to a significant increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer and have led to a revolution in cancer testing and treatment. What about the CFTR gene which codes for a protein that regulates the movement of salt and water in and out of cells? Mutations result in thick, sticky mucus that can clog airways and lead to respiratory and digestive problems known as cystic fibrosis.

There’s the APOE gene which, if you have a certain variant, will increase the likelihood of your getting Alzheimer’s as you age by eighty-five percent. There are also genes which give us protection against disease, such as PCSK9, the gene which encodes an enzyme that plays a crucial role in cholesterol metabolism. This enzyme binds to low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors on the surface of liver cells, leading to their degradation. LDL receptors are responsible for removing this LDL, often referred to as "bad cholesterol," from the bloodstream.

The names of these genes passed through my mind in a flash. They were the talk of many of our shows. What does John Dupre mean does the gene really exist? But he was a philosopher, and I was just a podcaster. I listened on.

Dupre argued that the gene was really no more than a handy term for biologists that takes on meaning based on a specific context.

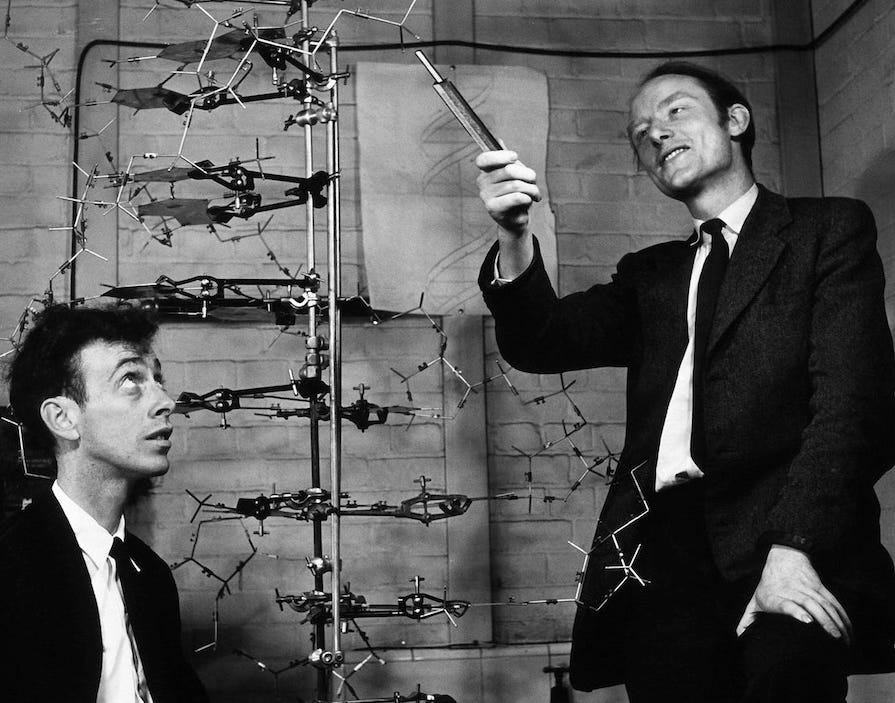

But wait a minute, even so, what about the Mendelian laws of inheritance? Surely there is predictability from genotype to phenotype. The gene is a discrete material thing, the code for the protein as Watson and Crick discovered—with the help of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins. It seemed to me that Dupre was questioning the foundation of biology.

This seemed to be a warning sign that there could be turbulence ahead on the high seas of biology. Did I want to hear more of this challenge? You bet I did—you know, the way when we start a movie on Amazon Prime the first thing that appears is a warning in the top left corner just as the movie begins: sex, nudity, profanity, drugs, swearing. Is it a warning or a promise?

“The gene is a model, just as Bohr presented his model of the atom,” John Dupre went on.

Well that made sense. Yes, we have our model of the atom, but still atoms are actually there. Physicists can weigh the protons and find the electrons. Wait a minute. Ah ha. Perhaps we do have a problem.

John Dupre concluded saying that the gene is whatever scientists say it is.

That sounded too subjective to me for a solid science like biology. However, the comparison with physics was sinking in. Quantum physics tells us that the location of the electron depends upon the observer. Furthermore, I had been podcasting long enough to pick up from biologists that research into the human genome was not leading to the breakthroughs in basic biology, health and disease that they had expected.

I pushed the red phone icon and hung up the Skype interview with John Dupre and went on a long run. One of the foundations of my thinking had just suffered a large crack. It might even be crumbling. Who would I turn to? Richard Dawkins and his great book The Selfish Gene? Yes, surely that would do the trick. Dawkins has been one of the most influential biologists of the 20th and 21st centuries. His book asserting the gene as the core unit of natural selection has sold millions of copies and influenced generations of not only scientists, but educated Liberals as well.

That was a joke. Kind of. I kid the Republicans!

But perhaps the joke is on me. I smile now at my older self. There I was, host of a podcast devoted to genetics calling ourselves Mendelspod, and the fundamental unit of biology--and of my podcast, thank you very much--had been called into question. Surely the mid-life crisis I suffered in the next year would have happened anyway. I was a gay man at 40. But this was speeding it along. I felt like I had come “smack” up against a wall after twenty or so years of pretty good speed.

Materialism and Beyond

What was the wall? What was the problem? I would discover in a few years that this interview with the philosopher John Dupre had made me question my own belief in materialism, if not realism.

Materialism is a philosophical term referring to a belief that matter - material - is all there is in the universe. There is nothing else. Richard Dawkins is a materialist. Most scientists are materialists. There are the exceptions, a notable one being Francis Collins, the scientist who led the National Institutes of Health through the genomic revolution. He is an evangelical Christian.

I’m thinking now that I had been a materialist since my college days, and that the conversation with Dupre brought up such a significant challenge that I began looking for another ontology, or view on “what is." If genes are not material things, but models, then my view of what existed in the world must include models as well as matter—for models are not matter.

And as I say, this did make some sense when contemplating my rudimentary knowledge of physics, especially quantum physics.

So what about Richard Dawkin’s assertion that genes are the core unit of life, of natural selection? What about my podcasting audience? What about my podcast!?

We had been advertising the show as “a front row seat to The Century of Biology." Our audience was mostly scientists who do research into genetics and genomics. The show is named after Gregor Mendel, the Czech monk who discovered genetics in the 1860s in his back garden when he wasn’t brewing beer. What about Mendel’s work and also the discovery of the structure of DNA, the double helix, by Watson and Crick? Surely there was more to this than just a “concept" or a “model."

The Gene

In 1868 Mendel published a paper in a little known journal showing that traits are inherited as discrete units—what would soon be called “genes”--and that each organism carries two “alleles” for each trait, one received from each parent. These alleles segregate during the formation of gametes--sperm and egg cells—so that each gamete carries only one allele for each trait.

There are few laws in biology. This law of segregation is considered one of them.

Mendel also found that the inheritance of one trait is independent of the inheritance of other traits. This means that the alleles for different traits are distributed to gametes independently of each other. This leads to genetic variation. Mendel observed that some traits are dominant and will always be expressed if at least one dominant allele is present, while other traits are recessive and only expressed if both alleles are recessive. Hence, his table about the color of sweet pea blossoms showing the probability based on lineage. Through his meticulous breeding experiments with pea plants followed probably by a little beer brewing, Mendel established the fundamental principles for the field of genetics.

Incidentally, Mendel’s work would go unnoticed for a generation.

As biology entered the 20th century, scientists like Walter Sutton and Theodor Boveri linked Mendel’s factors to chromosomes, the thread-like structures within cells. This is the period that saw the gene conceptualized as distinct entities neatly arranged on these chromosomes, much like beads on a string. It was, incidentally, the era of quantum physics where the model of the atom was being seen as separate from the material atom. Biology would have to wait for its “quantum” moment. The chromosomal theory was a significant leap, providing a tangible structure to Mendel’s abstract factors.

The one gene-one enzyme hypothesis, proposed by George Beadle and Edward Tatum in the 1940s, would further refine this view. They suggested that each gene was responsible for producing a single enzyme, drawing a direct line from genes to specific biochemical functions. We might say this was akin to discovering that each page of a cookbook contained a single, essential recipe for the body’s biochemical kitchen.

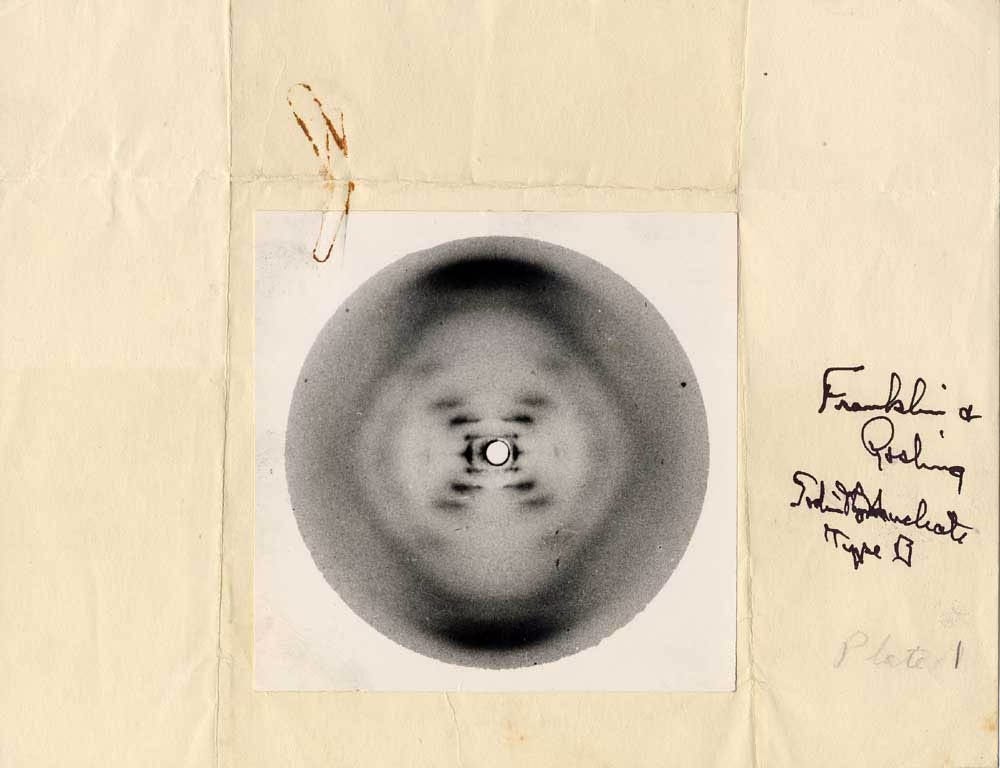

The mid-20th century brought the molecular revolution in biology. In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick, aided by Rosalind Franklin’s critical X-ray diffraction images, unveiled the double helix structure of DNA. This discovery was like opening the cover of the book of life, revealing the elegant script within. Much would be made of the fact that DNA was a sequence of four letters—what could be called a code. Was life information at its foundation?

The genetic code, cracked by researchers like Marshall Nirenberg and Heinrich Matthaei in the 1960s, showed how sequences of DNA nucleotides correspond to specific amino acids in proteins. Genes were now seen as blueprints, precise instructions for building proteins, much like detailed architectural plans for constructing a house.

Francis Crick’s central dogma of molecular biology, stating that genetic information flows from DNA to RNA to protein, framed genes as static instructions passed along a conveyor belt of biological machinery. This era cemented the gene’s role as the master script of life. It also cemented the metaphor of machine as central to biology.

This was the highpoint for what philsophers call reductionism in bioology--the belief that biology can be reduced to chemistry and from there to physics. In fact, the century preceding had seen the reduction of chemistry to physics, two milestones being the publication of the periodic table in 1869 three years after Mendels’s big publication and the Bohr model of the atom in 1913.

From then on in the history, genetics gets more complicated. The discovery of gene regulation mechanisms in the 1960s and 1970s, such as the operon model in bacteria described by François Jacob and Jacques Monod, revealed that genes could be switched on and off in response to environmental cues. Genes were now no longer just passive blueprints; they were dynamic actors responding to the director’s cues in the biological theater.

The discovery of split genes in 1977, with coding regions called exons interrupted by non-coding regions called introns, added another layer of complexity. To go with the theater metaphor, this was like finding that the script of a play included hidden directions and behind-the-scenes notes, making the narrative far more intricate than previously imagined.

The turn of the millennium brought the ambitious Human Genome Project headed by the aforementioned Francis Collins. With this project, mankind mapped the entire 3 billion letters of his own genome. It turns out that this project revealed fewer genes than expected (20,000 vs 100,000) and highlighted vast non-coding regions, often dismissed as “junk DNA” which, in fact, comprised around 96% of the genome. However, this so-called junk turned out to be crucial, playing roles in regulation and genome organization. (Genomicists still argue intensely about this point.). We began our Mendelspod podcast the year of the first ENCODE paper which aimed to characterize this junk portion of the genome. With this project, we discovered that previously overlooked weeds and critters in the garden, it turns out, are essential to its health and biodiversity.

Epigenetics, the study of changes in gene expression without altering the DNA sequence, further complicated the picture. Epigenetic modifications are like annotations in the margins of the genetic script, influencing how the story is read without changing the actual words. These modifications can be influenced by environmental factors, highlighting the interplay between nature and nurture.

Today, geneticists talk of systems biology, emphasizing interactions of genes within complex networks. Genes are no longer isolated instructions but part of a larger complex adaptive system. This holistic perspective is akin to viewing a garden not just as individual plants but as a thriving ecosystem, each component interconnected and interdependent.

One might say that biology for the past fifty years has been moving away from reductionism.

The concept of the gene over the last century and a half has traversed from reductionism, where genes were seen as simple, isolated units, to holism, where they are part of an integrated, dynamic system. The gene-centric reductionist view, popularized by Richard Dawkins, is now competing alongside a more organism-centric perspective.

Next month, we will launch our 14th season of the Mendelspod show with a series called, The New Biology. I will be interviewing the anti-reductionist Mike Levin, who argues for a new focus on the cell and the interaction of cell networks. We hope also to speak with Denis Noble, another anti-reductionist in the U.K.

Here I have aimed to give an overview of the journey in biology since Mendel and my own development over the past decade and a half. Our understanding of the gene has gone from an early conceptual framework, started by Mendel, to a more materialist reductionist view peaking with Watson and Crick’s discovery of the structure of DNA. In our day, the notion of genes has returned to a more conceptualist view, the view of philosophers of biology like John Dupre who argue that the gene is a human constructed model more than it is a discrete material thing. The tension between these two views is very palpable today in what might be called the post genomic era, and it promises an exciting and surprising future for biology, the study of nature and of life.

Note: Please send me any comments or questions about today’s article, and I’m always eager to take suggestions for new content. Email theraltimpson AT gmail DOT com.