I Went to See Cancer Cells and Found Kant and Locke Debating

As on many days in my time as a science journalist, I found myself yesterday afternoon in a glass-walled laboratory at MIT, where the hum of sequencers was steady as rain on a roof in Autumn. The Koch Institute feels less like the dark dungeons of test tubes and pipettes we knew when I was a student in the 80s and more like an airport control tower — screens glowing, glass everywhere, the impression of constant motion.

Dr. Elena Vargas greeted me at the door. She was in her forties, sleeves rolled up, lab coat hanging half open as if it were an afterthought. I noticed her nails were short, unpolished, stained faintly with dye. Her hair was dark and natural. Her eyes were part of that impenetrable scientific wilderness that I knew I would never be a part of.

Yes, I could occasionally glimpse the wilderness they saw, but never could see it from their wild eyes. Once you go down the English Literature major path in college, you become separated from other worlds forever. But I digress.

“This is where the strange secrets of cancer give themselves up?” I asked, my reporter’s instinct slipping into easy but hopefully provocative banter.

She sported an accommodating grin. “More like where we chase them — and they run just fast enough to keep us working late.”

It happens to be the case that I continually marvel at the scientist’s command of metaphor.

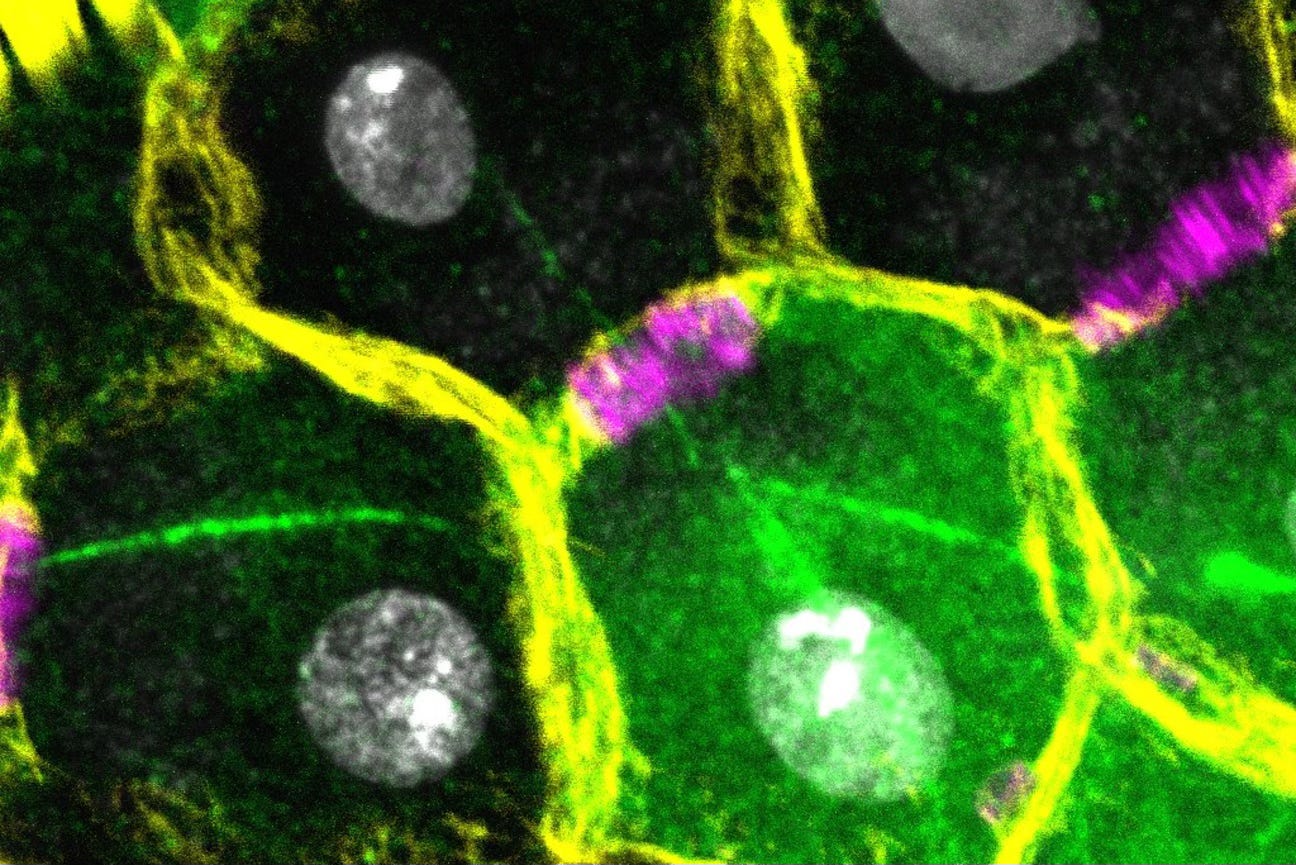

I chuckled aloud. We walked past several benches, students bent over their experiments. One postdoc was piping samples into a 96-well plate with the steady hand of a monk at prayer. (Is this the wrong metaphor?) Elena stopped in front of a glowing 3D map on a screen, neon colors of green, yellow and purple shifting with strange life.

“This is the study I wanted to show you,” she said, tapping the screen. “We’ve been mapping the proteome of breast cancer cells under drug treatment — at single-cell resolution, in their microenvironment. Not just the genes, not just the transcripts. The actual proteins doing the work.”

“You’ve told me before that if the genome is the script of the play, the proteins are the performance,” I recalled, happy to follow along.

“Yes,” and she zoomed in on a cluster of cells. “See this? These tumor cells are overexpressing PD-L1 — no surprise, that’s how they keep T-cells at bay. But look here.” She highlighted another set of cells, stromal fibroblasts wrapped around the tumor. “They’re pumping out Galectin-9, which amplifies PD-L1’s immune suppression. That interaction was hidden until now.”

I leaned in. “So it’s not just the tumor cells— the neighborhood of these cells matters. The Google map of the cell here.”

“Exactly. Cancer recruits locally. And if you only look at DNA, you miss the whole performance.” She paused, enjoying my journalist scribbling—as many interviewees do. “Here’s the kicker: when we treat with a PROTAC molecule targeting Galectin-9 — a little degrader that tags the protein for destruction — the whole system shifts. PD-L1 signaling drops. T-cells rush back in. In mouse models, tumors shrink fast.”

I must have made a sound, because she laughed. “Don’t look so startled. We didn’t cure cancer. But we opened a door.”

Elena had told me before that we will never “cure” cancer. We will just delay its harmful effects so that the patient dies of something else instead. Cancer is becoming more and more a chronic disease.

She flipped the display to a time-course graph. “Six hours after treatment, STAT3 phosphorylation in tumor cells falls by 60%. At twelve, NF-κB signaling dampens. By forty-eight hours, Caspase-3 cleavage shows up — apoptosis, the death cascade. But here’s the twist: it doesn’t happen in every cell. Some clones resist entirely. That heterogeneity—that difference from on cancer cell to the other— is the reality you only see through proteomics.”

I felt the thrill I always chase as a journalist — the moment the jargon dissolves and the story bursts open. “You’re not just watching genes misbehave. You’re watching life write and rewrite itself in real time.”

Elena’s eyes softened, and I knew she would step down to my level. “Yes. That’s what biology is: fidelity and improvisation. DNA gives us the structure, the rules of base-pairing and proofreading. But proteins — they’re history unfolding, the casting about, the variations that make every tumor, every patient, unique.”

I jotted “structure and history” in my notebook and underlined it twice. This was especially fascinating to me as I had been up late the night before reading of philosophical tension between Locke and Kant. Locke postulated that we come into the world with a blank slate, tabula rosa, and that experience creates all our knowledge, including that which comes from reasoning. How could we come with reason built in, or innate, when it takes reasoning some time to figure things out, he provocatively asked. Kant responded a hundred years later that, yes, knowledge comes only through experience over time, but that we must have abilities “structurally” built in at birth in order to receive experience. This included the sense of space and time. Today in this MIT lab on the Charles River it seemed that this tension between the structural and the historical exists at the biological level as well with the genome—and the proteome.

“Cancer is what happens when the structure frays and the history runs wild,” Elena went on to say. “That’s why it’s devastating. But it’s also why studying it teaches us what life itself is made of. If we didn’t allow for mutations, we’d never have become humans. Was cancer one of the bargains life made?”

We moved to another workstation where a time-lapse video played: cells dimming, flaring, signaling as the drug took hold. I’m still contemplating Elena’s last metaphor—life as a bargainer. How much of biology is expressed metaphorically? Is it fundamental to scientific thought, to all thought! And what if it is? Does the non-literal make our understanding any less real?

“Watch,” she whispered. “First the proteins quiet down. Then one pathway reignites — as if the cell were saying, Not so fast. We block one note, but the melody keeps going.”

I couldn’t look away. “You make it sound almost artistic.” I must let her know what I am thinking as well.

She tilted her head. “Maybe it is. Biology is yet another way of listening to the universe.”

We laughed together, though it wasn’t a joke. Outside, the Charles River was catching the late afternoon light through the large windows, leaving me with a sense of physical beauty that matched the wonder I felt at what I’d seen on the screen. I turned again to see the proteins flickering, restless, slowly revealing their secrets. I left thinking I had met Kant and Locke in the lab — structure and history spiraling together, like the DNA helix of life itself.