"I Exist. And This Is Good." Listening Again to Brahms's First Symphony

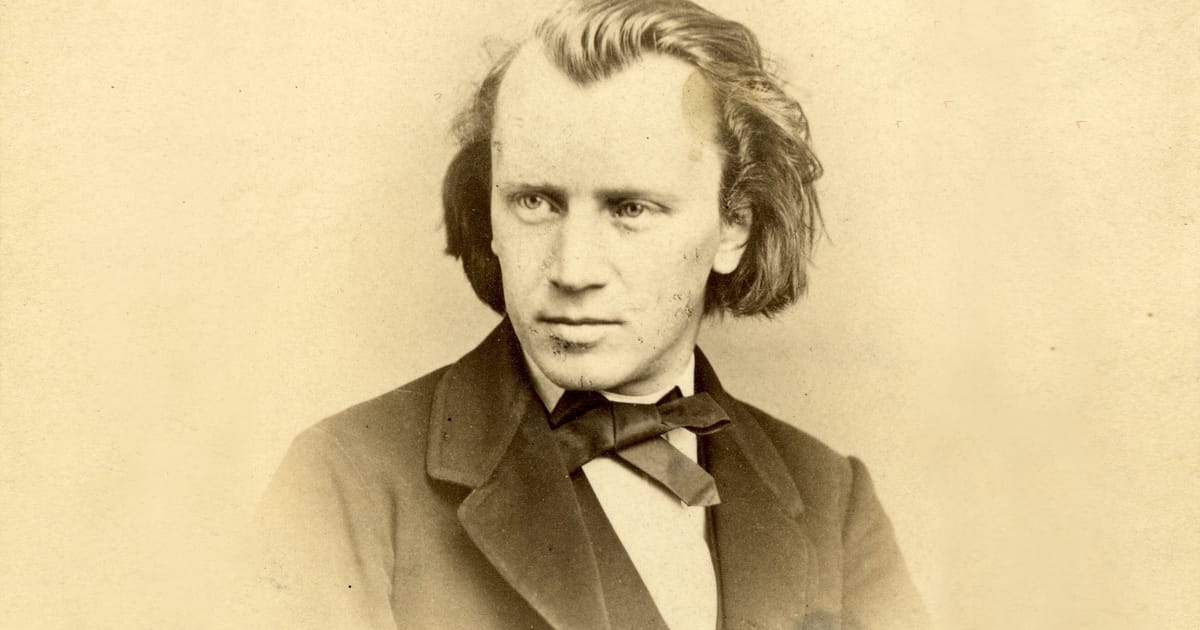

There are too few moments in this existence where we open up to the big truths. I’ve recently been listening to Symphony No. 1 of Johannes Brahms (1833-1897).

Perhaps you’ll let me persuade you to take a listen. This piece represents the apotheosis of the classical symphonic form. It is not just the triumph of the individual against one’s demons, it is the triumph of goodness itself.

It can’t hurt to be reminded of not just the goodness of things, of nature, of our friends, of food and life, but of the existence of goodness. Like many artists, Brahms could be a bit alfresco. He regularly skewered his friends and colleagues. When the composer Max Bruch played through his huge oratorio Odysseus for Brahms and turned eagerly for a response, Brahms said: “Hey, where do you get your music paper? First rate!” Brahms famously never married, preferring the brothel. But you’ll come away from this piece believing like never before in humanity and full of the wonder of creation.

In an earlier life, I studied to be an orchestral conductor. My teacher, Jorge Mester, was one of America’s leading conducting pedagogues and a protege of Leonard Bernstein. The Brahms First was part of my training. Coming back to it twenty years later, my appreciation has deepened. This symphony is an artistic achievement comparable to Dante’s Divine Comedy or Milton’s Paradise Lost. If it was a movie, it would be Star Wars or Bridge Over the River Kwai. It exists in a rarified orbit.

Brahms built on the tradition that came before, that of Beethoven, Mozart, and Haydn. When it premiered, Brahms's First Symphony was called Beethoven’s 10th. It took him twenty years to write because his contemporaries were expecting a piece worthy of the Beethoven tradition. In the last movement, Brahms writes a tune similar to Beethoven’s brotherhood theme from the Ninth Symphony. However, in Brahms's hands, the symphonic form becomes more emotional as it represents the individual struggle with identity, loneliness, and death, ultimately ending in community and redemption.

Let us talk about the classical tradition. What Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven achieved before Brahms was to move music from being the accompaniment to the events of our lives to being the main event itself. These composers were great because they insisted that music exists on its own, not as the background, but as an independent language capable of representing all facets of not only the human experience but all things. Beethoven’s coffin was carried through the streets of Vienna with twenty thousand followers because his music became the ultimate language. It went beyond words or pictures.

Today we have the movies, the combination of all three. But take yourself back to Brahms's day before any motion picture. Brahm’s First begins with a slow, tortuous introduction. We are in a grand space, contemplating the creation, perhaps seeing it: the unfolding slog of existence. The kettledrum beats incessantly, inevitably like a primitive dance around the fire, like the heart, like the forward motion of time itself. Things are conjured from the deep. This is the stirring of the void before God said, “Let there be light.” The strings climb up in painful chromatic steps while the winds cut brutally against them in the other direction. Slowly. Struggling. Why are we struggling here at the outset?

Give yourself a treat and do listen to the piece. Pour a bath.

My favorite recording of the moment is this one, Bernstein conducting in Vienna at the end of his life. These players have Brahms in their bones. Classical music is their religion. Bernstein cathartically reaches for all possible meaning from the piece, from his life. He conducts here like God himself moving his hands over the elements.

First movements of classical symphonies represent the individual, the personal struggle, and what it means to have a unique identity. Once the human mind evolved to include “the self,” that self was immediately challenged. We can find relief in the community and others. We can find relief in a loving relationship. For Brahms, that was Clara Schumann. But ultimately we exist as separate creatures, alone, in our minds. We must all pursue what it means to be an individual, to explore being a living creature with this mind whose power does not let us sleep, and we must face the demons. This struggle is as regular as the drumbeat of the introduction.

Why does Brahms begin the piece with struggle? Why the strife all the way through? It’s often remarked that we come into this life in pain and tears, and that’s the way we leave it. The universe itself was torn into existence. We must fight to be alive, to be who we are. The forces of opposition, the demons are not shy.

The individual of this first movement is someone who is not caught off guard by these dark forces. This piece took twenty years to write—Brahms is a man acquainted with his demons. He personally struggled with the bold and utter comprehensiveness—and incomprehensiveness-- of the nine symphonies of Beethoven. What composer can achieve anything after such a master?

First movements ask the question "What exists?"—first movements are metaphysical. Not only about struggle, they are also about the excitement of discovery and curiosity. Listen to the main theme rotating between the third and the sixth like an electron in orbit. Do electrons struggle too? At 6:13 the calm of the development section is dramatically interrupted by Brahms’s fist on the table: yum pum pum, “I am here . . . This is me . . .” returning us to the main theme in a direct undoubted realization of the self, such as that of Descartes.

If first movements are primarily from the head, second movements come from the heart. It’s a chance to give free rein to one’s emotions, to be here in the human world, a time to feel depressed and ecstatic and then quiet. There are often allusions to nature in the second movements of classical symphonies. And it is not just brute nature, but the sweet setting of a garden, a walk through the wildflower meadow in summer, sunsets on a Montana lake. We revel in our own personal sweet connection with nature. You hear this in Beethoven and in Mozart. Often with Mozart, he is crying while the sunflowers beam their beauty. Peace comes in the second movement from exploring and satisfying the movement of the heart, not the head. We are more than rational creatures.

Second movements can also be the place where the human heart opens up to another. They are about love, about being lovers, or any beautiful relationship, such as siblings. Here in the Brahms, the oboe is the single heart taking flight up above the earth, yearning, hopeful. Sharing one’s heart becomes a noble endeavor, not a capitulation. After the oboe laments the melody, the strings catch the heart pulling it up again in an e major triad of dignity and purpose before descending in sweet dance.

Third movements, indeed, are the dance itself. Now we are in the countryside with the folk. We enjoy our immediate community. We breathe in the joy of the local wedding or the village square at festival time. It’s the church crowd. It’s the 4th of July parade and waltz. And it happens in the dance meter of 3/4 timing.

Beethoven took his third movements to Scherzo, which is too fast for a dance. Scherzos are crazy and wild. Movement three of the Brahms is a return to the gentle sweet dance of Haydn and Mozart. Brahms chooses to calm his heart in the Gemutlichkeit of the village folk out together at night on the sidewalk.

Often the last movement puts the communal dance on a grander stage, the dance of all humanity. In Brahms's 4th movement, he takes us first back to the individual. There is to be more struggle. Per aspera, ad astra: in great tribulation we achieve great heights. The setting is now more stark than in the first movement. The individual climbs to a new peak and looks over the edge, contemplating death. Darkness ascends. Evil appears. And what is this evil, this dark force, this death? It is that which threatens not only our personal identity but threatens all of us.

We are in good hands. In the final movement, Brahms breaks free from the clutches of darkness. This is the journey of the First Symphony.

There are many variations in the tradition. Other composers will take us on a different journey. Shostakovich and Mahler may end in defeat, end in death, and quietness. Not so with Brahms. After the encounter with darkness, the sun comes out with pure light, beauty, and just goodness in a C major melody. Given to the horns, the brightest and sunniest of all the instruments in the orchestra, this moment is one of the most well known in all of music. The individual finds his footing. The flutes pick up tune with a breezy piercing clarity of the blue sky over the mountaintop. The horns blaze back the redemption of humanity. You will sob at the supreme integrity of this warmth and love. Some may call it the love of god. Some may say it is pure elation and ecstasy of nature. For three movements and an intro, we have climbed and climbed. Now we arrive at the top of Everest. There is no more anger, no struggle, only clarity. We see the view. And we see that the view is good. Let there be light!

This is goodness beyond pleasure. It is the deep joy at being alive and the recognition that there are good things, there are deep values in the world. It is said that Brahms took this theme from the folk alphorn players in the Swiss Alps. You know, those long horns twenty feet in length being blown by ruddy carefree mountain folk. It is the music of those who lived generations at the top of the world.

This would be a fine place to end the symphony, but in the symphonic tradition, Brahms brings us back to the community and the light turns into a Lutheran hymn from the brass. We now hear the church choir of our youth. Finally, everyone will join in singing the simple unifying tune of truth that many have compared to the final tune of joy in Beethoven’s Ninth. The strings play it first, pulling it up from their low g beginning in the interval of a fourth, the most hopeful and uplifting interval in tonal music.

As we sing our hearts out with pure meaning and bliss, we are no longer within the local village choir, the small circle at church where we grew up as children. Now we sing as a member of all humanity. We are again unified with Beethoven’s great hymn to brotherhood from a couple of generations previous.

There will be a final struggle. This is Brahms. A challenge to the individual will become a threat to all of mankind, our full annihilation, the end of everything we know. Global warming. The collapse of the universe. No! says Brahms, as he lifts us up into pure spirit. The goodness theme returns, then a final dance toward the end--not death, but our common future. Brahms repeats the hymn a second time which then gives into a final march, a final dance into the heavens, now a wild Scherzo of ecstatic energy.

Brahms will take up the challenge of the symphonic form three more times before his own end. It is a form that has released the powerful voices of our greatest composers. They give us something which we cannot get in philosophy, in religion, in scholarship—we cannot get it in words. The composer sings from intuition. And when it is this good, it is so powerful that our hearts glory in unison. Words, a lecture, a sermon, a political speech: we humans will pick them apart. But there is no denying the sheer beauty of orchestral sound, the music that Brahms conjures from crafted strings and wooden boxes. We accept it with recognition, in full tears, and a joyful heart and mind. We’re ready for tomorrow!