Has AI Hit a Major Roadblock?

Several lawsuits claim the new generative AI infringes copyright.

Whenever new technology comes out of the gate, it threatens to eat up as much of our lunch as it delivers, so awesome is the perceived power.

A lot of the fear around the new generative AI has now subsided, as has its hype. Instead, we increasingly hear about small steps of progress the new AI is making in medicine or manufacturing. Importantly, we have learned in the past year that the new AI could face a major setback. Remember that pesky little legal protection for originality called “copyright?” And remember the music platform Napster, which became an overnight sensation for sharing mostly pirated songs only to fall into the dustbin of history?

There are now several corporate and class action lawsuits which are claiming that the training of large language models (LLMs) on material that is protected by copyright is not “fair use.” Therefore, it should be prohibited. So far, there are no major rulings on it, but if judges decide in favor of these plaintiffs, the future of AI could be upended.

We had to know that something this powerful was too good to be true. The Wild West of AI will most likely be carved up and regulated. A new sheriff is in town in the form of old law. It is anticipated that Congress will probably weigh in with some legislative action to provide clarity and balance to the value of copyrights with the need for AI companies to train on ever more data. That is bound to be a long process, not without ups and downs.

One of these lawsuits was filed on December 27, 2023, by The New York Times. This suit alleges that OpenAI used millions of Times articles to train its AI models. This was an unauthorized use of published work without paying any licensing fee. The Times has listed 100 examples of GPT-4 memorizing content verbatim from the newspaper’s articles.

Interestingly, we also learned in the suit that The New York Times tried to reach a negotiated deal for compensation with OpenAI in April and the following months, but it didn’t go anywhere. It’s no wonder that OpenAI didn’t cooperate. Imagine the considerable list of entities that they would need to pay at this point.

At issue here, and it’s a very real issue, is the oceans of copyrighted data the bots have vacuumed up for their training. This data comes from everywhere. It is internet searches, digital libraries, tv and radio, social media, and databases. Some of those who have copyrights, such as Sarah Silverman, the comedian and now a plaintiff in her own case, are claiming that their work is used without their consent or compensation. They’re not even given credit.

There has been some attempt on Google’s part to give credit after they were slapped with a lawsuit for their new search. Having taken over 91 percent of the search market, Google has been testing a major change to its interface, the “Search Generative Experience” (SGE), using an AI plagiarism engine that grabs facts and snippets of text from a variety of sites, cobbles them together (often word-for-word) and passes off the work as Google’s creation. Bad Google.

According to an article in the Economist,

"It is a legal minefield with implications that extend beyond the creative industries to any business where machine-learning plays a role, such as self-driving cars, medical diagnostics, factory robotics and insurance-risk management. The European Union, true to bureaucratic form, has a directive on copyright that refers to data-mining (written before the recent bot boom). Experts say America lacks case history specific to generative ai. Instead, it has competing theories about whether or not data-mining without licences is permissible under the “fair use” doctrine.”

It is easy to understand the argument of the artists and news organizations such as the Times asking for compensation or at least some kind of credit. But what of the advocates for “fair use” who favor the new generative AI? How do they see it? They argue that "fair use" essentially allows for infringement of a copyright when it is done for a limited and transformative purpose. They say that “training" is the equivalent of "learning from," and we’d never say that reading a book and learning from it violates copyright law.

Take note: Napster also tried to deploy “fair use” as a defense in America, and they failed.

Typically, the courts have attempted to balance "fair use "with guidelines such as the purpose and character of the use, including whether it is for commercial or educational purposes. What is the amount and substantiality of the portion used of the protected material? And what will be the effect on the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work?

So what will be the answer? How will the courts rule? Experts and creatives have cited AI’s potential to replace artists and transform work methods as destabilizing for markets of creative products. Conversely, AI has great potential to support artists’ development and accelerate creative industries. A letter published by Creative Comments and signed by artists states, “Just like previous innovations, these tools lower barriers in creating art…”

In the journal Texas Law Review, authors Mark Lemely and Bryan Casey write that it is a critical roadblock for AI and that the industry could die in its infancy. For them, it is one of the most important legal questions of the century: “Will copyright allow robots to learn?”

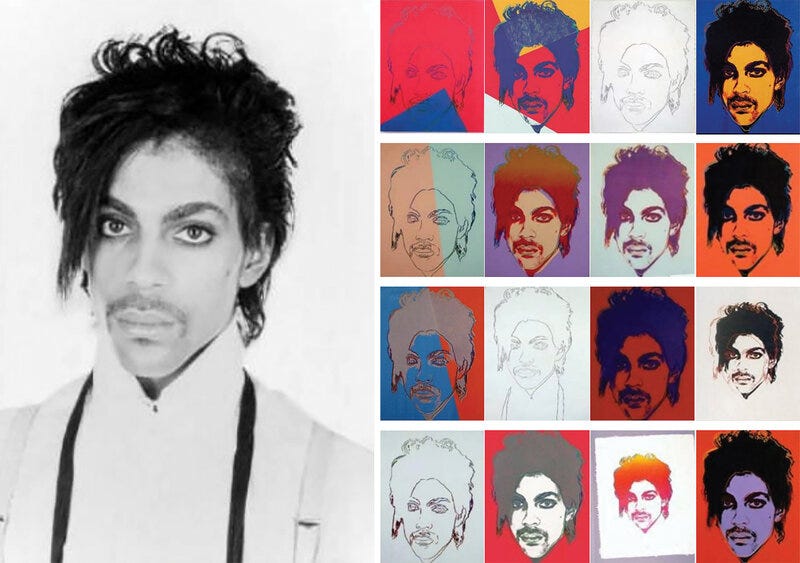

Perhaps some guidance will come from a recent ruling from the Supreme Court. Last year, the high court ruled 7-2 that the late Andy Warhol infringed on a photographer’s copyright when he created a series of six silkscreens based on a photograph of the late singer, Prince.

Writing for the majority opinion, Justice Sotomayor said that both Goldsmith’s photo and Warhol’s silk screen are used to depict Prince in magazine stories and share “substantially the same purpose,” even if Warhol altered the artist’s expression. “If an original work and a secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes,” and they are both used in a “commercial nature,” Justice Sonya Sotomayor writes, it is unlikely that “fair use” applies.

Writing for the minority, Justice Elena Kagan said that the majority looked past the fact that the silkscreen and the photo do not have the same “aesthetic characteristics” and did not “convey the same meaning.” All the majority cared about, she said, was the commercial purpose of the work. “Artists don’t create all on their own; they cannot do what they do without borrowing from or otherwise making use of the work of others,” she said. The majority opinion will “impede new art and music and literature” and “thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge,” she added. “It will make our world poorer.”

Was she thinking of the new AI?

In another related case, a federal judge in Washington D.C. upheld last year the U.S. Copyright Office's rejection of a copyright application for an art piece created autonomously by an AI system. Computer scientist Stephen Thaler tried to get a copyright for a piece of visual art titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise.” He created the piece using a computer system called the “Creativity Machine.” Thaler wanted to transfer the copyright from the AI to himself. But Judge Beryl A. Howell found that the U.S. Copyright Office was correct in denying copyright protections to a work created entirely without human involvement. The ruling could be a critical component in future legal fights as lawyers test the limits of intellectual property laws when applied to AI.

I sympathize with the artists and news organizations bringing these copyright suits. AI poses a major threat to the livelihood and dignity of those who create original text and art. The power of AI to vacuum vast amounts of text and instantly reproduce it will undoubtedly have a dynamic future. We want to be able to make productive use of new technology, but not when it violates ethical norms. Why should we hold AI to a lower standard than we do each other?

And we are, in the end, dealing with each other. There is no rogue or sentient AI.