A Symposium: On Beauty

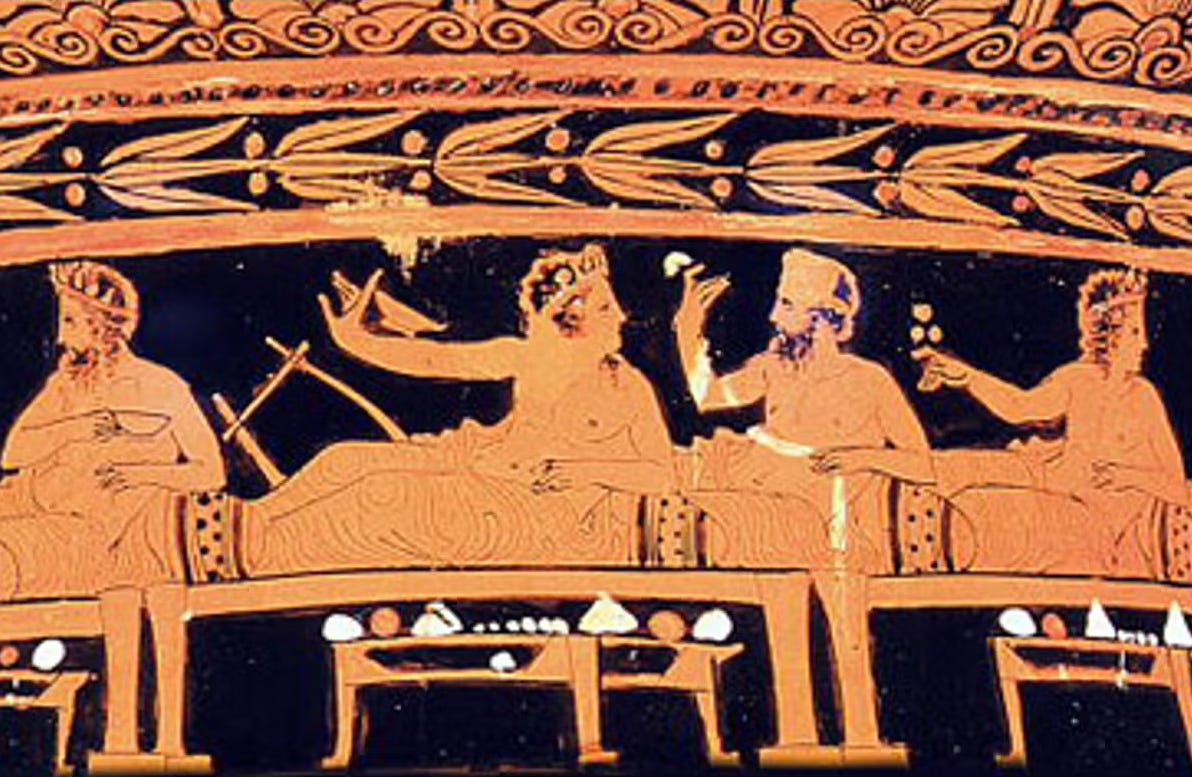

In the warm glow of an Athenian evening with a full moon rising above the distant Parthenon, a group of friends reclined on couches, the air fragrant with myrrh, torch fire, and red wine. Tonight’s symposium was not about love, as the great Socrates once debated, but about beauty.

Callista the Sharp-Eyed, sharp-tongued and unyielding, knew that the presence of females was already causing tension, so she volunteered first. “Beauty is merely attraction. It is biological desire. When we see a beautiful young man, do we not wish to possess him? To take him in our arms?” She cast a furtive glance at Alexios the Golden, the radiant youth among them, whose very presence seemed to confirm her argument. “A white ghost slug may not be beautiful to us, but to its mate, lured by pheromones, it is irresistible. Beauty is nature’s cunning trick. An extension of desire, born from selection and survival.”

Alexios the Golden smiled, unshaken. “Then what of an exquisitely painted vase, Callista? Or the stars arranged in a perfect constellation? Is it your biological desire that makes them beautiful?” He leaned forward, his golden hair catching the firelight. “You say beauty is attraction, yet attraction shifts from person to person. You find me beautiful, but another may not. Have we not taken beauty beyond its animal origins? What of the beauty in virtue, in wisdom, in art?”

Callista’s eyes flicked up and down his frame. “Whatever you say will be adorable, because you are adorable, Alexios.”

He laughed with discomfort. “But what if I were a devotee of a cruel king? A tyrant who crushes cities? Would I still be beautiful?”

At this, Demetrios the Wine-Lover, a man of indulgence and mirth, swirled the wine in his cup. “Behold, the beauty of the wine,” he mused. “Its deep crimson hue, the way it catches the light, the way it caresses the lips. It has no mind, no virtue, yet we call it beautiful. Beauty, then, is in the eye of the beholder, is it not?”

Callista scoffed, waving a hand. “Spare the clichés, Demetrios. The eye is mere biology. Light enters, signals fire, the brain interprets. There is no mystery, only function.” Was the evening to be dominated by Callista, the others wondered.

Demetrios chuckled. “Ah, Callista, ever the reductionist. Yes, the oculus—pardon my Latin—is biology. But when we speak of the eye, do we not often mean the eye of the mind? When we look back upon our past with fondness, when we see not with our eyes but with memory, is this not beauty? Beauty does not only reside in an object outside ourselves that must be perceived—it can be the very fabric of recollection, the way time burnishes moments into something finer.”

Lysandra the Silver-Voiced, a poet, tilted her head thoughtfully. "If beauty exists within us as well as without, does it then become something we create as much as something we observe?" She leaned forward. “And if beauty is mere perception, then does beauty even exist in the external world beyond our gaze? If I write a verse and no one hears it, does it hold beauty in itself? Homer himself wrote of beauty—Helen, whose face launched a thousand ships. Was it her beauty that caused war, or the power that men projected upon it?”

Nikos the Geometer, a mathematician, added, “And what of symmetry? Harmony? The ratio of the golden mean? The gods themselves sculpted the world upon it. Surely, beauty is not only attraction, nor mere perception, but something with structure, something absolute.”

Alexios the Golden, who had been quietly contemplating, finally spoke. "I've been wondering," he mused, "if beauty isn't related to health. But not just the health of the body, Callista. Also of the mind and soul."

He leaned forward, his voice measured. "Let's say I see a painting, and I'm immediately drawn to its beauty. For a moment, it lifts me above this mere world of brutish biology, eat others or be eaten. We might say it is good for me. Or, let's say I see a painting, but I don't immediately recognize its beauty. Yet, upon learning about the artist and what he was after, I begin to understand something beautiful about it. Is this not good for me on a deep level?"

Callista smirked. "I've been attracted to plenty of beautiful things which are not good for me, Alexios. Beauty can be a mean bastard. And I can even take delight in that."

Thus the discussion swirled with Callista heavy on the heels of Alexios the Golden, each argument weaving into the next, until a sudden question cut through the revelry:

“Would you prefer power to beauty?”

Silence settled over them. There was only the flickering of the torch flames. Each of the night’s revelers turned inward, weighing the question.

Then, at last, Callista broke the hush. “According to biology, beauty is somewhat important. But from the ugliness around us, it isn’t everything. Look at those in power today—are they beautiful? Do they even appreciate beauty?”

Alexios, ever serene, murmured, “Beauty is a higher power.” He let the words settle, then continued, "Power commands, it bends the world to its will. But beauty—beauty draws us in without force, without coercion. A king may order obedience, but a truly beautiful soul inspires devotion freely given. Beauty can stir men to build temples, to write poetry, to act with kindness when they might otherwise be cruel. It reaches beyond the self, beyond brute survival, and calls us toward something greater."

With these lines, Callista was speechless for once. Was she contemplating the fact that Alexios had something more than mere biological attraction?

“Yet power consumes beauty,” Nikos mused. “The fat old tyrant takes the beautiful young concubine. The statues of Apollo are placed in his garden. The warlord wears the gleaming armor crafted by the finest smiths. Isn’t beauty merely a trinket to power?”

“Or does beauty grant power?” Demetrios countered. “A ruler with no splendor is easily forgotten. We remember Pericles, not only for his mind, but for the grandeur he built around him. The gods themselves are honored not just for their might, but for the terrible and wondrous beauty they possess.”

Lysandra sat up, her silver voice ringing. “There are levels to beauty. The beauty of the body, transient as the petals of a rose. The beauty of art, which lingers in the memory. The beauty of wisdom, which deepens with time. And beyond all, the beauty of the universe itself, the divine symmetry that governs all things.”

“Perhaps the highest beauty,” mused Nikos, “is not in the object, but in the act of beholding. To appreciate beauty is to transcend power, to step beyond the brutal struggle of control and submission.” He paused, then looked to his companions. “If I may, let me tell you a story.”

The others nodded, and Nikos began.

“Once, I journeyed to the ancient kingdom of Myria, where the ruins of its once-great palaces lay overgrown with vines, the lovely foliage making a quiet mockery of the power that had reigned there. As I wandered, I entered a forgotten temple, and inside stood the throne of the last king, still intact, its many-colored gems glinting in the dim light. It was protected by the local villagers, who had long since reclaimed the land from royalty but still honored the beauty of the throne.

One of the villagers, an old man, approached and told me a tale. Long ago, the king had summoned the finest gem setter in the land, a master craftsman named Lycanus, to construct the throne. The king desired a seat more splendid than any other, a thing of unmatched beauty. And so Lycanus worked, setting each gem with patient care, his hands guided by something beyond mere duty.

One day, as Lycanus was at work, the king himself entered the chamber. Everyone bowed—everyone except the artist, who continued his labor, unshaken. The king frowned and said, ‘Lycanus, I could have you beheaded for this indignant lack of respect. Why do you not bow? I am the king, and you are a mere craftsman.’

Without looking up, Lycanus replied, ‘Your Highness, when I am working to create beauty and art, there is no king.’”

Nikos let the words have their effect, watching his companions’ faces in the lamp light as they considered the tale.

The wine was nearly gone. For a moment, none spoke. Then Lysandra the Silver-Tongued lifted her cup and smiled.

“We are fortunate, then,” she said, “for we have all beheld beauty tonight.”